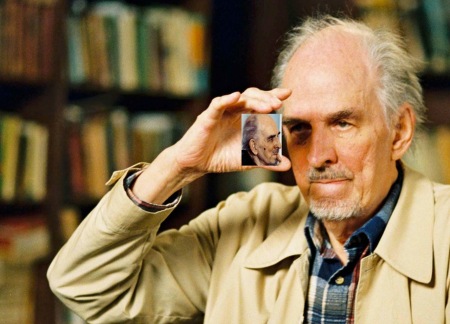

Ingmar Bergman – In Memoriam

“Ingmar Bergman is dead.”

“Isn’t she the one who was in Casablanca? How sad.”

“No, that was Ingrid Bergman. Ingmar Bergman was a man.”

“Oh, I see. Was he Ingrid’s father?”

Philistinism can be so infuriating. Especially cinematic philistinism, to a cinephile like me. But I imagine that when the legendary director from Sweden died last month at the age of 89, many conversations in the vein of the one above must have followed. Bergman was a deservedly acknowledged and much lauded master of the cinema – the Academy loved him, awarding him a record three Best Foreign Language Film Oscars (a record bested only by Federico Fellini’s four wins), he in turn is idolized by innumerable filmmakers, Woody Allen and our very own Mehreen Jabbar among them – but I would venture that fewer and fewer younger people know who he was. We, as a species, are forgetful (ergo all the repeating of history); well, our loss I say. If the blog generation is unfamiliar with the connotations of the adjective ‘Bergmanesque’, then they are poorer for it.

My first brush with Bergman came when I was twelve – that’s what comes of being born in a family with a strong arty ‘brought-up’. Having ditched school because of a non-existent stomach ache, and finding myself alone and bored, I happened to pop into our spanking new VCR a tape of Fanny and Alexander (1982), which was a good choice since, as I was to learn much later, some have called that Bergman’s most accessible film (‘foreign’ films, it seems, are generally incomprehensible to mere mortals). One moment from it took my breath away and has stayed with me since: the two children of the title are playing hide-and-seek on a quiet afternoon in the family home. Alexander, hiding underneath a table, peeks out and glances at a marble statue that has fascinated and haunted his imagination forever. Then, as his eyes pop in wonder, the statue moves… I was enchanted.

My second encounter with Bergman occurred almost a decade later when, as a student at film school, I saw Cries and Whispers (1972), the first of only three foreign language films ever nominated for a Best Film Oscar. A film of immense visceral power and visual beauty, it shocked with its stark and brutal view of human frailty and hypocrisy.

It was a far cry from the gentle and nostalgic lyricism of Fanny and Alexander. All the more intriguing because Cries and Whispers had been made a full ten years before Fanny and Alexander. Like so many artists, it seemed Bergman too had mellowed with age, the latter film reading like an ode filled with a longing to return to a more innocent, gentle age. Indeed, he expressed just such a yearning some years later: “I’m deeply fixated on my childhood. Some impressions are extremely vivid, light, smell, and all. There are moments when I can wander through my childhood’s landscape, through rooms long ago, remember how they were furnished, where the pictures hung on the walls, the way the light fell. It’s like a film – little scraps of a film, which I set running and which I can reconstruct to the last detail – except their smell.”Bergman himself, of course, was often far from gentle in his appraisals of fellow members of the film fraternity. He famously turned up his nose at Italian impressionist Michelangelo Antonioni: “He’s done two masterpieces, you don’t have to bother with the rest… [Though there are brilliant moments in his films] Antonioni never really learned the trade. He concentrated on single images, never realizing that film is a rhythmic flow of images, a movement. I never understood why Antonioni was so incredibly applauded. And I thought his muse Monica Vitti was a terrible actress.” He also expressed derision for Hollywood’s ‘boy wonder’ Orson Welles calling him “a hoax”, and his revered opus Citizen Kane “empty, dead, a total bore… The amount of respect that movie’s got is absolutely unbelievable.” He was, however, impressed with Spielberg, Scorsese and Coppola, and held the highest regard for Russian filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky calling him “the greatest of them all.” Fellini, too, found favour with the Swede: “He is intuitive; he is creative; he is an enormous force.”

So what does Bergmanesque actually mean? The director himself said that it implied a preference for intuition over intellect, as well as the exploration of themes of mortality, loneliness, and faith. The notion of female sexuality was also often at the core of his films, most notably in Persona (1966), perhaps his most experimental and uncharacteristic film, for visually, his work tended to be direct and austere, rather than overtly stylized . His actors were often encouraged to improvise dialogue, and his propensity for capturing them in extreme close-up became his trademark, as did his dynamic lighting technique. Most importantly, though, he seemed to use his films as an instrument of personal catharsis, infusing them with an emotional resonance that is almost unparalleled.

For a time, Bergman fell out of favour with his champions, both among his audience as well as film critics. The emotionality of his work became an easy target, just as Chaplin’s penchant for pathos had also lost him fans in the post-70s Reaganesque climate. As in so many other instances, though, critics reconnected with his work in the late 90s, and he was proclaimed the world’s greatest living filmmaker by Time magazine, in 2005. From the Grim Reaper of The Seventh Seal (1957), and Van Halen’s song of the same name, to being a target of loving parody in everything from The Simpsons to French and Saunders, without even being aware of it, a number of our cultural markers come from Bergman’s films.

And that is immortality.

Leave a comment